Generative AI has been the subject of remarkable claims, including about how it is already putting millions of jobs at risk. Is that really likely?

The first problem for HR is just knowing what we are actually talking about with AI. The most common definition is computer-generated information that only humans could be expected to produce, something that is obviously a moving target. When people say they are using AI, then, it’s hard to know what they are talking about. Just asking them whether they are using it leads to answers that are not interpretable: Is an applicant tracking system considered AI? Are chatbots? Or even my Word processor?

Gen AI has a more straightforward definition: computer systems that generate original—and we should add, sensible—content. The most important of which for jobs is text content like ChatGPT (although if you are in the much more focused design world, gen AI content is a huge issue).

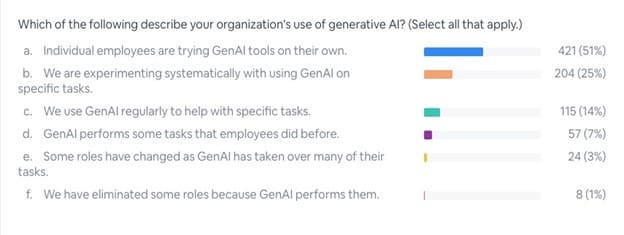

The survey results asking about use are still quite confusing here because the questions aren’t very clear. At MIT’s Work/24 online conference earlier this month, I asked about 800 conference participants how their organizations were using gen AI; these are participants whom—given the conference theme—we might think are, if anything, more likely than average to be using gen AI.

Are these big numbers? If you are doing an internet search and you hit the right button on Google in Microsoft Edge now, the answer you get is from gen AI—so, you are using it. We might then expect the number of people using gen AI to be huge. That 51% are trying it does not seem big. The fact that only 1% report that it has taken over a job is still a big number—especially if you are in that 1%—but it does not look like the Armageddon predictions we often hear.

Yes, you might say, but it’s only beginning. I’m not sure I agree with that. Has anyone not heard of it by now? And it is free to try out.

Problems with gen AI predictions

The problem with big claims about the effects of technology, especially AI, on jobs is the assumption that if something is possible in theory, then it will happen in practice. Just as the claims from 2018 that driverless trucks would by now eliminate virtually all truck driving jobs, the claims about what gen AI—and especially text models like ChatGPT—will do also make that assumption. But at the same time, they ignore whether a gen AI solution is actually an improvement. My colleagues and I have written about this at some length elsewhere.

Consider, for example, the claim that gen AI tools can take over the mundane tasks of writing correspondence to customers and employees. They could, but those tasks have already been automated. No one is writing that letter you get from your power company. Form letters cleared by lawyers handle most of those tasks now.

Well, how about call center jobs? There are lots of those. Call center employees already follow standard scripts that drop down based on what customers say, and chatbots have already taken over much of that work. Could gen AI models make even better chatbots to help clients and customers with their problems? Probably, but companies don’t seem to have much interest in spending to improve customer service, and they certainly don’t want chatbots “freelancing” and coming up with novel solutions to customer problems (as Air Canada discovered when its chatbot gave customers fares lower than what the company wanted).

Learn more about gen AI’s impact on HR at the upcoming HR Technology Online, June 12-13.

A more general problem is that almost no jobs involve a single writing task. Computer programmers, for example, would seem to be the most vulnerable to gen AI, as tools like it seem able to pull up code suited to a programming task quickly and easily. But it turns out that programmers only spend about a third of their time on actual programming. Most of it is spent on basic administrative tasks, and the programming time is largely spent figuring out what clients and the organization really need. Software that pulls up possible code for programmers has been around for a while, and initial studies of gen AI’s effect on programming indicate that it saves time in some tasks—but not all—and adds time to others. Useful, probably yes. Revolutionary, probably not.

Even if a gen AI tool took over a task completely, that does not make it possible to cut jobs. Say it saves 10% of a programmer’s time. Can you cut 10% of a programmer? If they are an hourly paid contractor maybe, but not if they are salaried employees, as most office workers are. Could you consolidate those programming jobs? Only if you had 10 completely interchangeable employees—not just on programming tasks but others as well—and the tasks could be organized such that they could be spread evenly across the remaining nine workers.

Let’s not ignore the fact that these gen AI tools are conceptually, and in practice, a huge leap forward. They may be very useful in allowing us to solve new problems. But that does not mean that current jobs will go away.

The post Gen AI and job losses: What’s the real story? appeared first on HR Executive.