As the country slowly returns to work, the pandemic may end up trapping recruiters in a legal snare called immunity discrimination.

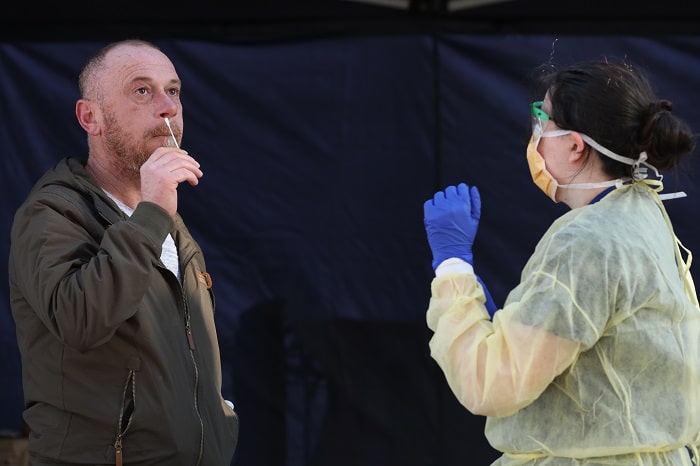

(Photo by Asanka Ratnayake/Getty Images)

This new type of bias involves recruiters who favor job candidates who have already contracted and survived COVID-19. Research suggests that coronavirus reinfection is doubtful. So, unlike applicants who haven’t had the virus, survivors likely won’t need time off work to recover from any future infection and can safely travel, meet with clients or work with others to complete tasks or long-term projects.

“Recruiters may be inclined to lean toward one candidate who survived COVID-19,” says David Barron, partner at the Cozen O’Connor law firm. “It’s very dangerous to make decisions based on the past health history of candidates. It would not be appropriate for employers to know if someone has had COVID-19 in the past and use that information for purposes of making an employment decision.”

The Equal Employment Opportunity Commission has already chosen sides, stating this practice is unlawful, he says.

Related: Employers’ latest quandary: COVID-19 vaccines

Meanwhile, some job seekers may take full advantage of their health history by mentioning their COVID-19 experiences to recruiters during interviews, hoping it gives them an edge over their competitors.

Barron says recruiters need to handle such scenarios in the same way they deal with other out-of-bounds topics, such as religion: Politely steer the conversation in a different direction.

The safest approach is to avoid discussing COVID-19 during interviews, he says, except for addressing company policies like requiring all workers to wear masks or to social distance.

Barron explains that any question HR would normally ask employees can be posed to job candidates. For example, it’s legal to ask applicants if they are currently experiencing any COVID symptoms but taboo to ask broad questions, such as whether they have any underlying health conditions.

“We haven’t seen a lot of this litigation yet, but it’s starting to percolate,” says Barron, adding that such cases will come “awfully close” to those involving a rarely used law called GINA, or the Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act, which prohibits genetic discrimination by employers and health insurers.

In the months ahead, immunity discrimination may also rear its head in different ways. Barron points to managers who inadvertently use this information when deciding promotions, handing out stretch assignments or determining which employees to bring back to the office.

See also: Navigating the legal questions of workplace returns

“It’s going to be hard for managers to not think about this when they’re making workplace decisions,” says Barron. “It’s a good time to train people to make sure they understand the rules of the road.”